By Dr Minh Alexander, NHS whistleblower and former consultant psychiatrist, 19 February 2021

Summary: Dr Ambreen Malik a consultant psychiatrist employed by the private provider Cygnet Health Care, has been found on 1 February 2021 by the Employment Tribunal to have suffered multiple whistleblower detriments and unfair dismissal over a baseless allegation of gross misconduct. She had insisted on telling a coroner’s inquest of the full facts about a Cygnet inpatient death, in which staff failed to search a patient after a visit, but then discovered what appeared to be an illicit drug in his hospital room after he died. The Employment Tribunal criticised several Cygnet managers for their part in reprisal against Dr Malik as a whistleblower, including several directors. The ET determined that the CEO, the director of human resources, the then medical director and the regional operations director (now listed as Managing Director, Healthcare Division North and a board member), had variously acted in “bad faith” and/or were “less than honest” or not truthful in the prosecution of a case against Dr Malik or were untruthful in evidence to the ET. The ET was critical of Cygnet’s referral of Dr Malik to the General Medical Council, which it determined was a detriment for whistleblowing. The ET concluded that Cygnet managers had seized an opportunity to dismiss Dr Malik after her whistleblowing:“It is clear that this was however the general background to the respondent’s senior managers disliking her, and later seizing an opportunity to dismiss her.” But puzzlingly, the ET stopped short of finding that Dr Malik was dismissed because of her whistleblowing. The case is yet more evidence in support of UK whistleblowing law reform.

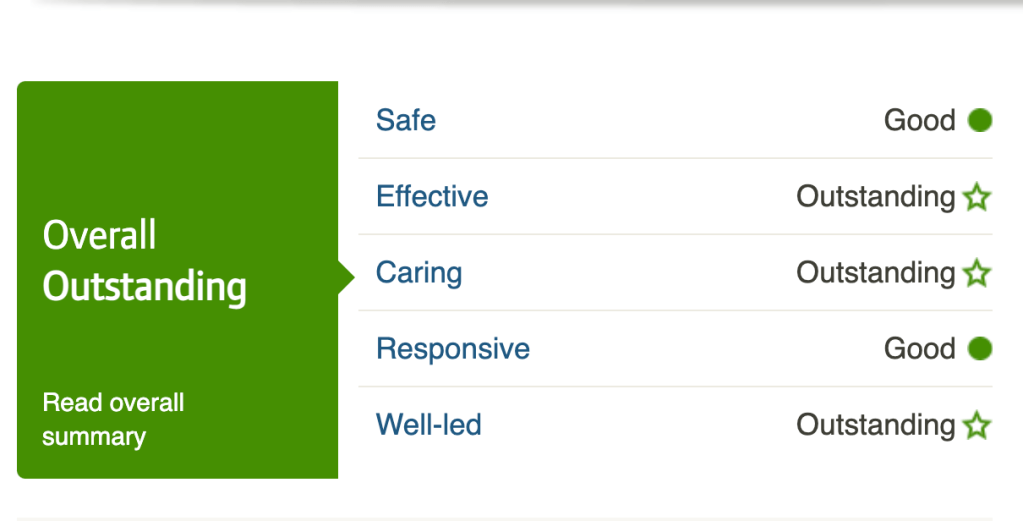

On 31 December 2019 the Care Quality Commission rated the unit where Dr Malik worked, Cygnet Fountains Blackburn, as ‘Outstanding’ overall and outstandingly well led. This is despite the CQC also finding from a specific well led review undertaken in July/August 2019 that there were leadership failures at Cygnet.

NHS England commissions specialist mental health services such as those provided by Cygnet. There are serious questions about NHS England’s performance as a commissioner, especially given that commissioning failures were previously identified by an independent investigation of a homicide of a patient by a fellow patient on a Cygnet unit.

Cygnet was the provider operating Whorlton Hall and Newbus Grange care facilities, when patients were abused in 2019.

Background

Whistleblower mistreatment is a problem across all sectors, but perhaps is particularly likely to occur in profit driven care environments.

The full extent of the whistleblowing governance problems in private healthcare is hidden by ruthless suppression and a fearful workforce.

These problems are likely to affect the future health landscape more as the government seizes greater control of the NHS, and looks to be preparing for de-regulation.

Cygnet is a UK based company, providing private mental health services, that since 2014 has been owned by the US private health giant Universal Health Services.

Cygnet is a very large provider of mental health and learning disability services, with over 113 sites in England, Scotland and Wales.

The CEO of Universal Health Services reportedly “earned £39.5 million in 2016” and Tony Romero the CEO of Cygnet reportedly earned £625,000 in 2019.

Cygnet has been mired in scandals, regarding care failings, avoidable deaths, patient abuse and excessive executive pay.

Some of the Cygnet scandals are listed below:

Importantly, Cygnet owns Whorlton Hall and Newbus Grange. Patients were abused at both facilities under Cygnet’s ownership. In May 2019 BBC Panorama exposed serious abuse of vulnerable patients at Whorlton Hall. This led to the NMC issuing interim suspension orders against three members of Whorlton Hall nursing staff, arrests and a police investigation.

Alongside this, a worker at Newbus Grange was caught assaulting residents from March 2019 onwards, and eventually received a prison sentence:

‘Sadistic bully’ from Darlington assaulted Newbus Grange residents

On 28 February 2019 the Care Quality Commission dubiously rated Newbus Grange as ‘Outstanding’:

Eight months later on 24 October 2019, CQC had drastically downgraded the rating to ‘Inadequate’.

CQC were forced to undertake a review of Cygnet’s leadership in response to the multiple care scandals, much as they had been forced to review the provider Castlebeck after the 2011 Winterbourne View scandal. The CQC review of Cygnet’s leadership, undertaken in July/August 2019 but not published until January 2020, concluded there were problems with accountability:

“Governance structures and processes were not effective in supporting good quality and sustainable services… A clear line of accountability from the “ward to board” could not be established across all of Cygnet Health Care’s locations. Governance systems and processes had not prevented or identified significant issues within locations to allow effective intervention by the executive team.”

“Governance systems and processes were not effective in maintaining sustainable and high-quality care. The systems and processes in place had not prevented or identified significant issues in locations which have resulted in breaches of regulation and hospitals being placed into special measures due to inadequate ratings.”

“Not all the required checks had been carried out to ensure that directors and members of the executive board were “fit and proper”.

But incongruously, CQC glossed over Cygnet’s suppression of staff concerns and praised its culture:

“A culture of openness was encouraged by leaders and embedded within policy. Most staff knew what should be reported and felt able to do so.”

And despite the slew of scandals, many Cygnet facilities are currently rated ‘Good’ or ‘Outstanding’ by CQC.

One of these ‘Outstanding’ psychiatric facilities, Cygnet Fountains in Blackburn Lancashire, has been found guilty by an Employment Tribunal, through a judgment issued on 1 February 2021, of serious whistleblower reprisal and the unfair dismissal of a whistleblowing doctor.

Cygnet’s CEO, the then medical director (now reportedly retired), Human Resources Director and the then regional operations director (now managing director, Healthcare Division North) were criticised for malpractice and reprisal.

The ET remarked of Cygnet’s CEO: “We found Dr Romero’s actions to be less than honest.”

The CEO and human resources director were criticised for bad faith. The ET found that the medical director made an “untrue” referral of the whistleblower to the General Medical Council. It also found that the regional operations director and other Cygnet staff were untruthful in their evidence to an internal investigation. The ET rejected some of the evidence given by the regional operations director during proceedings:

“101. We do not find that Mr Ruffley’s evidence with regard to asserting that a legal opinion be sought was actually said to the claimant at the time. We have found this to be a back-covering comment inserted with hindsight.”

Other whistleblowers have raised concerns about Cygnet’s care standards. For example, in 2019, it emerged from an inquest that Taffy Mandizha, ward manager at Cygnet Coventry had repeatedly raised concerns about safe staffing. This included a concern raised a week before Claire Greaves, a detained inpatient took her life:

Poor governance by private providers such as Cygnet is especially important because they provide specialist locked facilities for patients with very special needs. These special needs are largely no longer catered for by the NHS. That is to say, private providers look after particularly vulnerable patients, isolated by detention and usually located out of area and far away from their families.

The whistleblower case of Dr Ambreen Malik

I will only summarise this complex case broadly. The full Employment Tribunal judgment about the facts of the case can be found here:

Dr Ambreen Malik v Cygnet Health Case No. 2403141/2018

Dr Ambreen Malik was a consultant psychiatrist employed at Cygnet Fountains hospital, in Blackburn Lancashire. She attracted the wrath of Cygnet management because she refused to look the other way over a failure of risk management by Cygnet.

In 2015, a patient died the day after receiving visitors. He was not searched by staff after the visit. After his death, a foil wrap of what appeared to be an illicit substance was found in his room. Dr Malik informed the medical director and the regional operations manager of the issue. She became increasingly concerned that the organisation was covering up the matter.

When she sought advice from Cygnet’s CEO ( who trained in psychiatry), he responded in a manner which she found threatening:

“43. The claimant then, on the same day, attempted to contact her line manager, Dr Leslie Burton, to raise her concerns. He was on leave and unavailable, as was the person who covered for him. She then made a disclosure by email to the Assistant Medical Director, Dr Bari, and to the CEO, Dr Tony Romero. Dr Romero’s reply the following day by email was to start with, “Are you telling me you will go to the police?” and ended with, “Do you know the implications of what you are saying?”. The claimant felt intimidated and bullied.”

An internal investigation was set up by Cygnet, which excluded Dr Malik and failed to involve the police or the family. The ET noted that Cygnet’s regional operations manager misled Dr Malik on these issues:

“44. Dr Romero did, however, set up an enquiry panel and 20 staff members were interviewed. The claimant was not one of them, nor were the police contacted, nor the deceased’s family. In spite of this Mr Ruffley advised the claimant that staff on duty, police and the deceased’s relatives had been interviewed, and no-one corroborated her observations. On three occasions the claimant was asked to apologise to members of staff. She refused because she knew what she had seen.”

Cygnet’s CEO later advised Dr Malik not to make her life “complicated”, with regards to her evidence to the coroner’s inquest:

“45. In March 2016 the claimant was called to attend the coroner’s inquest into the patient’s death. She had previously discussed the evidence that she would be giving to the coroner with Dr Romero, and asked for advice on how to proceed over the drugs found (as she believed it). His reply was that she should “do not make your life complicated” (bundle A pages 345-346).

Dr Malik was advised by Cygnet’s solicitor not to mention the discovery of drugs to the coroner, but she stood her ground and gave evidence about the discovery:

“46. The day before the inquest on 8 March 2016 the claimant met with Mr Parsons, a solicitor, at a briefing arranged for staff members due to give evidence the following day. The claimant asked him when and how to mention her discovery of the drugs. Mr Parsons indicated that it was not relevant to the patient’s death (bundle A pages 357-360). The claimant was left believing that the respondent was trying to cover up the discovery of drugs.

47. Prior to the start of the inquest on 9 March 2016 Mr Parsons and Ms Ngaaseke had a conversation with the claimant in which Mr Parsons advised the claimant that if she mentioned the discovery it would affect her credibility and that she must have mis-remembered the event. He went on to indicate that if she told the court about it, it would affect Mr Parsons’ credibility. The claimant approached the coroner’s clerk to ensure the coroner was asked to raise this issue with her. When asked about it by the coroner she narrated the sequence of events and her observations, including explaining that the subsequent internal enquiry did not corroborate her claim.”

Twelve days after giving the above evidence to the coroner, Dr Malik was suspended by the regional operations director on grounds of loss of trust. One of the accusations against her was that her evidence reportedly triggered a police investigation against Cygnet, and led the coroner to threaten Cygnet’s solicitor with a regulatory referral:

“49. On 21 March 2016 the claimant met the Group Medical Director, Dr Burton, and the Regional Operations Director, Mr Ruffley. She was advised there had been a breakdown of trust and she was being suspended because of the evidence she had given at the coroner’s inquest. She was told that the coroner had threatened to refer Mr Parsons to his regulator, and that Fountains was to be investigated by the police for hiding evidence and ‘higher ups were very upset by it’. This was confirmed in writing by a letter on the same date, which stated that she was suspended pending an investigation into the evidence she gave at the inquest and the effect it had had on relationships at Fountains.”

The ET determined that this suspension was a detriment against Dr Malik for making protected public interest disclosures.

It also concluded that other detriments followed, including:

a) Punitive publicising of her suspension by the medical director:

“On her return to work she discovered that an email had been sent about her by the Group Medical Director to all of the doctors within the organisation. It was admitted by Dr Romero that this had not been done before.”

b) Excessive, punitive supervision, established by the assistant medical director, medical director and CEO:

“56. Before the claimant returned to work, Drs Bari, Burton and Romero met and agreed a course of action. On her return, Dr Burton increased her supervision from six monthly to twice weekly”

c). Undermining of Dr Malik’s role by the hospital manager, through excluding her from important admission and discharge decisions, removing support for clinics, criticising her for being late and introducing a new deadline for reports.

d) The assistant medical director asked staff to covertly report on Dr Malik. For instance, a cleaner accused her of leaving a screen open in her office whilst she saw patient.

e) Removal of Dr Malik’s role as Clinical Appraisal Lead, by the medical director, against her wishes

f) Failure to ensure that a grievance by Dr Malik about whistleblower reprisal was progressed.

g) Being subjected to ostracisation such as hostile behaviour when she raised a concern about contributory organisational failings related to a patient suicide, and not being invited to clinical board meetings as previously agreed.

Cygnet additionally conceded that Dr Malik was subject to another detriment when the medical director later referred her to the General Medical Council. This referral was based on false allegations that she had failed to follow protocol on covert medication:

“79. The respondent referred the claimant to the GMC on 18 October 2017 after an incident, which is described in more detail below, led to her dismissal for gross misconduct.

80. The respondent denied in evidence referring the claimant to the GMC maliciously or without justifiable reason, but did accept the referral to the GMC is a detriment.”

The ET condemned the “defamatory” GMC referral by Dr Leslie Burton the medical director, which it considered was linked to Dr Malik’s protected disclosures:

“398. Dr Burton subsequently thought that the claimant was dishonest and told the GMC – a defamatory comment and one questions the motive behind that. He suggested that she had used the word “useless” about her line manager when she had never said any such thing.”

“418. We do, however, find that the additional detriment, of Dr Burton’s reference to the GMC on the day of dismissal was a detriment and is in time. The features contained within that referral and the note that he sent to the GMC link, were unpleasant and untrue, and formed a second detriment. They clearly reflected his view of the claimant following the earlier public interest disclosures. These were detriments because of an earlier public interest disclosure, and we find this to be both in time and made out. We note that the claimant’s appraisal did not reflect his damning assertions about the claimant.”

The ET described the tone of the medical director’s correspondence to the GMC as “venomous and dishonest” and it concluded that he had been “waiting” for a chance to make a referral:

“170. Mr Burton’s assessment of the situation with the GMC could not be regarded as honest and objective. An email sent by him on 13 October to Kate Harrison (Liaison Officer for the GMC) suggests a far from impartial stance. He described the claimant as “an opinionated woman”, and alleged there were rumours of bullying (contradicting her glowing appraisal from 17 July). None of her past actions which had caused concern would have merited a referral to the GMC, suggesting he had been waiting for this chance.”

Regarding the false allegations which led to the GMC referral and Dr Malik’s dismissal by Cygnet for gross misconduct, these related to her implementing a care plan of covert medication in an extreme case with risk of violence. This is a rare practice, but permitted and ethical in certain circumstances, with safeguards.

The ET found that the covert medication care plan implemented by Dr Malik was based on full multi-disciplinary consultation, including with Cygnet senior managers and the patient’s family, and it complied with policy. However, Cygnet manufactured a disciplinary case against her, with false claims by several individuals that she failed to follow procedure and did not consult adequately. Cygnet additionally accused her of bullying, a claim rejected by the ET.

The ET noted that Cygnet’s disciplinary case was very obviously flawed and contradicted by a mass of records which showed her to be innocent of the charges. It stated:

“423. We find that the investigation and disciplinary procedure were fatally flawed. In particular Mr Ruffley, who was dishonest in his information to the investigation and to the Tribunal. The decision making process was disreputable.”

The brother of the patient who was covertly medicated, who supported the care plan, gave evidence at the ET in Dr Malik’s favour.

The ET concluded there had been no gross misconduct by Dr Malik:

“434. We do not find the claimant guilty of gross misconduct in the light of our findings above. We therefore find that the respondent was in breach of contract in dismissing the claimant for gross misconduct. We find that the claimant followed the hospital’s policy and took note of the other policies. The policy of her employer was noted to be signed by Dr Burton but he appeared to have little or no knowledge of its content. We find it more likely than not that the hospital’s own policy was not actually read by the investigators, the dismissing offer or the appeal officer, and we are sure that Dr Burton was unaware of the contents of the policy that was signed off in his name. The reason for the dismissal was adequately explained in the venomous and dishonest tone of the email to the GMC link. A careful analysis of the steps she took showed that she had complied with every step required of her under the respondent’s own policy in the particular circumstances of M. Prudence may have suggested that other steps could be taken, taking legal advice for instance, but there was no requirement on her to do so. There was no evidence of wilfulness, or of gross negligence. The evidence suggested she was doing the best she could for her patient, as her contract required, and within the policies and statutes under which she was required to work The claimant was thus dismissed without notice in breach of contract.”

The ET criticised Cygnet managers responsible for the blatantly unfair disciplinary action against Dr Malik and her unwarranted dismissal.

The ET concluded that the interim hospital manager and the regional operations manager were dishonest about the case against Dr Malik:

“The investigators were not helped by the dishonesty of Serena Birtwhistle and Mr Ruffley.”

“We found Mr Ruffley to be less than truthful, and noted that there was evidence that he had lied in the investigation in that he denied he knew about the covert plan, and there was clear evidence in the emails that he did.”

The ET criticised the fact that Cygnet appointed an inexperienced peer of Dr Malik’s to hear her disciplinary case. It concluded that the decision to dismiss was in reality one of bad faith and had in fact been made by the CEO and the director of Human Resources.

“430. The matter was then compounded by Jenny Gibson’s involvement. She appears to have written both the dismissal letter and the appeal letter, and we find it more likely than not that she did both make the decision and write the decisions with Dr Romero. That cannot be within the range of reasonable responses, and shows a litany of bad faith.

431. The claimant was unable to attend her appeal because she was unwell. Dr Romero allegedly heard the appeal in her absence. He made a decision with regard to the administration of the drug O which had not been discussed with the claimant and was never put to her before the decision was taken. Jenny Gibson was again involved. There are no file notes at all of any discussions between her and any of the other people involved in the investigation, dismissal or appeal. We find that to be quite extraordinary for a senior HR manager. There were no notes either from Dr Romero of his part in the appeal, simply the letter we believe was prepared by Jenny Gibson which was signed by him. We do not say he played no part in that decision, but we find it to be a collaboration between Jenny Gibson and Dr Romero. The claimant, as she believed, did not stand a chance of the dismissal being overturned.”

Cygnet’s CEO heard Dr Malik’s appeal against dismissal even though there was an outstanding grievance by Dr Malik against him. The ET commented:

“We noted he [Dr Romero] chose to undertake the appeal himself, which he could have delegated to a manager immediately below him. We noted that the grievance was never heard – and is still outstanding to this day – and that Dr Romero was responsible in effect for nearly all of the actions taken by the other parties, through Jenny Gibson.”

The director of HR composed an outcome letter for the dismissing officer:

“Jenny Gibson sent an email to Dr Burton, Mr Ruffley, Dr Romero and Mr McQuaid in which she created some wording to send to Dr Malik in terms of why “we” had decided to dismiss her. She also sent a copy to Mr Boyapati “so that he is aware”.

162. Jenny Gibson was not the HR representative at the disciplinary hearing and did not credibly explain her intervention at this point, when given the opportunity. The rough notes of the reasons to dismiss were produced by Ms Gibson and sent to Dr Boyapati to approve. She selected very few issues and ignored the balance of the allegations and evidence. She gave a very partial account. The letter made no mention of the policy of the hospital, the NICE guidelines or the CQC (presumably because they could not say that she had failed to comply with them).”

The ET noted that the director of human resources’ draft letter of dismissal received the medical director’s approval:

“165. Dr Burton on receipt of the draft thanked Ms Gibson for “a good email. Dr Boyapati on receipt made a few minor changes. It is however completely clear that Dr Boyapati did not provide the wording as suggested by Ms Gibson, and that in fact the wording was hers.”

Illustrating how arbitrary Dr Malik’s treatment by Cygnet was, the medical director criticised her despite her adherence to Cygnet’s covert medication policy, which he himself had personally signed off the previous year:

“122. This policy was approved specifically by Dr L Burton who later appeared to be a serious critic of the claimant’s actions when she followed his policy.”

“The policy of her employer was noted to be signed by Dr Burton but he appeared to have little or no knowledge of its content. We find it more likely than not that the hospital’s own policy was not actually read by the investigators, the dismissing offer or the appeal officer, and we are sure that Dr Burton was unaware of the contents of the policy that was signed off in his name.”

In short, the ET concluded that Cygnet effectively commissioned “lies” and came to a predetermined decision to dismiss Dr Malik:

“It was done by only interviewing those who sided against the claimant, telling lies to the investigation and the tribunal, and by Drs Romero, Jenny Gibson and Dr Burton ensuring that the script for the dismissal and appeal was theirs.”

Sadly, as often seen, the ET stopped short of concluding that Dr Malik was dismissed for whistleblowing, even though it appeared to acknowledge that Cygnet had been waiting for an opportunity to dismiss her because of her previous whistleblowing:

“433. We do not therefore find that the respondent has proved on the balance of probabilities that there was a potentially fair reason for the dismissal or further that a fair procedure was followed. There may be an argument to follow on the issue of contribution. We do not find that the claimant was dismissed because she made public interest disclosures i.e. automatically. It is clear that this was however the general background to the respondent’s senior managers disliking her, and later seizing an opportunity to dismiss her.”

So there you have it, a case of proven conspiracy against a whistleblower which will seriously affect her career, but with no legal linkage made between the disclosures and the dismissal. This will mean as usual that any compensation will likely not reflect the real losses suffered by Dr Malik nor truly compensate for blacklisting that she may suffer.

Once again, Dr Malik’s case reveals graphically what a sustained ordeal whistleblowers may face, only to be failed again by weak whistleblowing law when they seek redress years later.

At present, highly paid executives often see unfairly sacking whistleblowers as a worthwhile risk, and the paltry compensation they have to pay harmed whistleblowers as simply the very reasonable price of doing unethical business.

There is often a chasm between corporate rhetoric and the reality of what happens behind closed doors. In a rapid response of 14 January 2020 to a BMJ article about Cygnet’s governance failings, Dr Tony Romero Cygnet CEO wrote:

“The board take any concerns raised very seriously and as a leadership team we promote honesty and transparency. The report cites a culture of openness and initiatives to encourage reporting of issues, including a whistleblowing line. It acknowledges most staff feel able to report incidents and raise any concerns, which demonstrates our lines of accountability are clearly understood. We are also appointing a freedom to speak up guardian.”

Whistleblowing law reform

The Malik case shows yet again why we need much stronger, proactive whistleblowing law that compels protection, a proper, timely response to whistleblowers’ protected disclosures and much stronger deterrence of cover ups and reprisal.

| A Westminster petition was previously set up seeking reform of and gathered only 1,462 signatures by the time of the six month expiry date on 17 February 2021. A new non time-limited petition has been set up: Replace weak UK whistleblowing law, and protect whistleblowers and the public Your help in signing and sharing this petition would be much appreciated. |

Commissioners and regulators

It is also vital that NHS commissioning oversight of high risk services such as those operated by Cygnet is improved, to protect vulnerable patients and to ensure best value for the public purse. There is currently a standard clause in NHS purchased private care, which requires private providers to have a basic level of whistleblowing governance. But does anyone really bother to track instances of whistleblower reprisal?

The local CCG, East Lancashire, seems to have been cheerleading instead of interrogating:

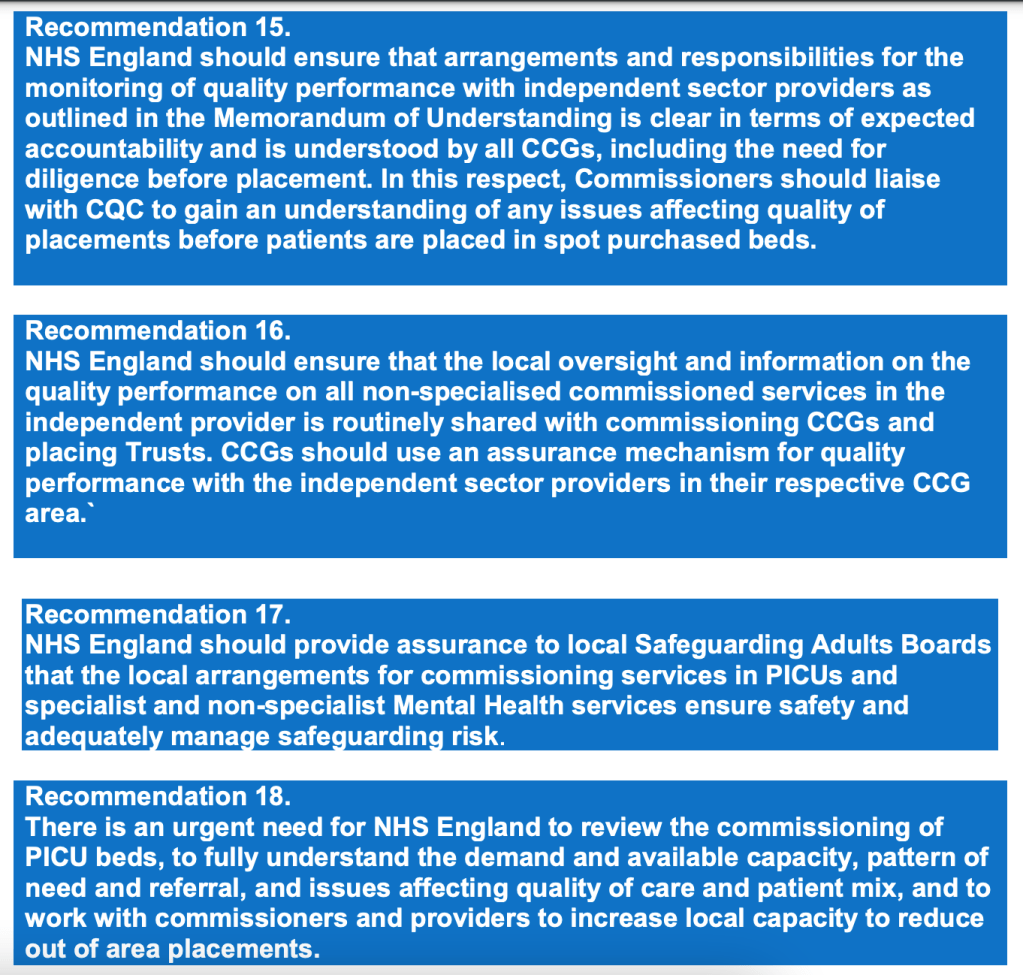

The NHS England-commissioned statutory independent homicide investigation under HSG (94)27 of an inpatient killing at Cygnet Bradford identified issues with NHS England’s oversight of outsourced mental health care. The homicide investigation report made the following recommendations:

CQC also has responsibility to check whether providers have safe culture, including good whistleblowing governance.

In an inspection report of 31 December 2019 CQC waxed lyrical about the leadership of Cygnet Fountains hospital:

“There was compassionate, inclusive and effective leadership at all levels. Leaders at all levels demonstrate the high levels of experience, capacity and capability needed to deliver excellent and sustainable care.

Comprehensive and successful leadership strategies were in place to ensure and sustain delivery and to develop the desired culture. Leaders had a deep understanding of issues, challenges and priorities in their service, and beyond.”

“Staff knew and understood the provider’s vision and values and how they were applied in the work of their team.

Staff were proud of the organisation as a place to work and spoke highly of the culture. Staff at all levels were actively encouraged to speak up and raise concerns, and all policies and procedures positively support this process.

Staff felt respected, supported and valued.”

The CQC inspection team responsible for this finding are not named:

Questions of regulatory capture arise, especially bearing in mind that a CQC manager ran away from the CQC circus in 2016, to join Danshell, one of Cygnet’s predecessor firms.

The managing director of Castlebeck Care, one of Cygnet’s predecessor organisations was banned by the Insolvency Service for eight years because he failed to act appropriately on whistleblowing disclosures about patient abuse at Winterbourne View hospital:

“Neil Cruickshank, the Managing Director of Castlebeck Care (Teesdale) Ltd, has been disqualified for 8 years for failing to follow proper company procedures regarding Quality of Care, after he was sent information from a whistleblower regarding the behaviour of staff at the Winterbourne View Nursing Home, near Bristol.”

Notoriously, the system regulator Care Quality Commission also failed the Winterbourne View whistleblowers:

The CQC is now responsible for operating CQC Regulation 5 Fit and Proper Persons (FPPR), under which providers must ensure their directors are fit and proper persons.

Will the CQC now break its habits of wilful blindness and inaction on FPPR, and act upon not just the suppression of protected disclosures but orchestrated whistleblower reprisal in Dr Malik’s case?

But perhaps there is nothing to worry about. Cygnet have appointed a Freedom To Speak Up Guardian, and speaking up will be “celebrated” henceforth.

Declaration of interest: Nick Ruffley was service director when I whistleblew about care and governance failings at St Andrews Healthcare, another private mental health provider.

RELATED ITEMS

Petition: Replace weak UK whistleblowing law and protect whistleblowers and the public

Contract Failures in Mental Health Services

Counting the cost of the CQC: Abuse, Whorlton Hall and CQC spin doctors

CQC Whorlton Hall Cover Up: More CQC responses & culpability

St. Andrews Healthcare, Whistleblowing, Safeguarding and Public Protection

Replacing the Public Interest Disclosure Act (PIDA)

I am so glad you have documented this sordid case which I hope will be studied by the culprits/executives involved as they weep whilst flagellating themselves.

Cygnet certainly matured into a very ugly duckling.

Nevertheless, let’s hope that Dr Ambreen Malik at least feels somewhat vindicated and can emerge from that particular murky area refreshed and aiming for a position more worthy of their talents and integrity.

LikeLike

This shows exactly the poor leadership at Cygnet, this is not just the the hospitals listed, any hospitals led by this leadership team are dangerous. I got out of there quick. A career destroying experience .

LikeLiked by 1 person