By Dr Minh Alexander NHS whistleblower and former consultant psychiatrist, 12 September 2018

|

Summary: UK whistleblowing law is utterly ineffective and fails to protect the public, or indeed whistleblowers. It needs to be replaced and the campaign continues: https://minhalexander.com/2018/07/18/replacing-the-public-interest-disclosure-act-pida/ But whenever law change is mooted, some hear opportunity knocking in a different way There has been increasing lobbying to import a US model of ‘whistleblowing’ bounties. This is a lucrative business but is a far departure from whistleblowing in its truest sense, and raises problems of ethics, fairness and the efficient use of public funds. There is insufficient data in the public domain on the effectiveness of US bounty schemes in protecting whistleblowers to conclude that they merit replication by the UK. The data that is available raises serious questions. The use of bounties would be particularly problematic in the public sector as the model conflicts with Nolan principles of selflessness and strict neutrality. This piece examines some of the background on bounties and a new All Party Parliamentary Group on whistleblowing. This APPG was established with financial contributions from a US bounty hunting law firm. Whistleblowers UK, a private company which has advocated for whistleblower rewards, has been paid by Constantine Cannon to act as APPG secretariat. |

Whistleblowing is a social good. The European Commission and others have defined it as work-based speaking up in the public interest.

For many years, whistleblowers were viewed with suspicion and seen as no better than ‘rats’, ‘snitches’ and ‘stool pigeons’.

There have been occasional examples of ‘whistleblowers’ who have themselves been implicated in wrongdoing, such as falsification of records or who were paid bounties despite conviction for criminal breaches. Bradley Birkenfeld was paid $104m in bounties for reporting a tax fraud under US IRS rules, but he withheld some of the relevant information during the resulting investigation. He was eventually jailed for his part in tax evasion.This paper discusses the issues around the Birkenfeld case and others in more detail:

But whistleblowing in its truest sense is altruistic, done in good faith and motivated only by the public interest.

That said, legal tests which require proof of utmost good faith are problematic, because they invite employers to attack whistleblowers’ character and fabricate smears.

There is also a wider public interest issue in ensuring that serious concerns are aired, even if motives may be ambiguous. For example, if whistleblowing disclosures are made in the context of an employment dispute.

But such pragmatic arguments can only be extended so far. The practice of actively incentivising whistleblowing with financial bounties is a much more ethically difficult matter. In the public sector, bounty models are incompatible with Nolan principles of selflessness, neutrality and the need for public servants to avoid any conflict of interest or actions motivated by personal gain. Bounties could undermine public trust.

In the health service, bounties for whistleblowing would conflict with the professional duty of candour and could erode public trust in healthcare professionals.

Bounty models would also cut across NHS contractual obligations introduced after the Winterbourne View scandal through changes in the NHS constitution, These require staff to raise concerns. From the public’s point of view, why should NHS staff be paid extra to do something which is already part of their job?

There are also practical problems with bounty models. They typically run on recovering financial assets, with a percentage of the spoils going to the person who raised the alarm. But how is such a model to work where there is no financial angle?

And how would it make sense to impose fines on a de-funded NHS that is little more than skin and bones, or take money from patient care for bounties? NHS Improvement has just admitted that English NHS trusts have an underlying deficit of £4.3billion.

Taking a prime example, the US False Claims Act 1863 (FCA) was an emergency measure passed during the American civil war to stem a tide of fraudulent defence sales to the Union. Senator Howard who proposed the Bill explained that it was intended to induce fraudsters to betray their co-conspirators for a cash bung.

“In short, I have based the…sections upon the old-fashioned idea of hold out a temptation,” and “setting a rogue to catch a rogue…a reward for the informer who comes into court and betrays his co-conspirator”

Or as one author drily put it, ‘Riches for Snitches’. The idea was for anyone to litigate on financial fraud against the US government, on behalf of the US government. These are known as ‘qui tam’ suits (‘qui tam pro domino rege quam pro se ipso in hac parte sequitur’ or ‘who brings the action for the king as well as himself’). Qui tam actions were deployed in medieval England as a crude means of law enforcement by citizens where the Crown provided little infrastructure. Qui tam legislation had long been abolished in England.

The original False Claims Act bounty set in 1863 was an eye watering 50% of all assets recovered. Rough and ready justice. Fair enough under the exigencies of war, but there are better governance tools in quieter times.

The FCA fell into disrepute in the Second World War due to unpatriotic, so-called ‘parasitic’ and opportunistic claims. Adventurers piggy backed private FCA claims onto government criminal actions against fraudsters, which added nothing to the public interest. After representations by a disgusted Attorney General, Congress hogtied the FCA legislation in 1943 and discouraged bounty hunting under this provision for over forty years.

This is a history of the FCA:

The FCA was revived in 1986 after scandals. This helped to spawn an industry which has netted billions in bounties. Bounties pay for claimants’ legal fees and a cut of the bounties typically go to specialist bounty hunting law firms. Phillips and Cohen one of the best known US bounty hunting law firms, reports that its whistleblowing suits have recovered over $12billion:

The modern FCA allows bounties of up to 30% of any money recovered by qui tam suits. The US government may join qui tam actions, ignore them or kick them out if, for example, they are considered ‘parasitic’ and a waste of public time and resources. An internal US Department of Justice memo from January 2018 reportedly revealed growing government impatience with the over-proliferation of FCA claims which are counter to the public interest.

According to US Departmen of Justice statistics, between 1986 and 2017 there were 11, 980 qui tam suits, which netted a total of $40,549,645,268 for the public purse. Of this, a total of $6,584,992,211(approximately 15%) was paid to bounty hunters.

Arithmetically, the US government is one up on the fraudsters. But is it right that vast amounts of precious public money have been given to individuals as bounties? Is appealing to greed the right way to tackle greed? Wasn’t legitimising greed and de-regulation of the markets part of the original problem? The jackpot model may get the government results, but also leaves some hungry. It is possible to be a genuine whistleblower who makes reasonable disclosures, but not to qualify for any award under a bounty scheme.

There is no complete, published dataset evident on the nature of FCA claims that have been made since 1986. The great majority of anecdotally reported cases feature financial fraud such as kickbacks and false billing. It is less common to come across FCA claims that are specifically about public safety. Arguments about fraud on the basis that the US government has been billed for health or social care that is so substandard that it is ‘worthless’ and constitutes fraud have been controversial. Some such claims have occasionally succeeded.

Regardless of whether such claims about substandard care succeed, the US government should arguably ensure that these concerns are passed to the relevant regulators as a matter of public protection. I asked the US Department of Justice if it tracked this category of claim and if it could furnish me with a list. It could not.

When the FCA was revived in 1986, anti-retaliation provision was added to the law, but there is no complete, published dataset evident on how whistleblowers have fared under these provisions. Unofficial sources suggest that only a minority of FCA claims result in bounties being awarded, and that many employees who whistleblow under the FCA have poor outcomes, which implies that protection has not been effective:

Whistleblowers, beware: Most claims end in disappointment and despair

There was even a totally bizarre case of Jeffrey Wertkin, a Department of Justice lawyer who was jailed for literally trying to sell out whistleblowers, who had claimed under the FCA, to their employers.

But markets march on. FCA claims need not be confined to US territory. They can be filed from abroad and this is a growing market:

Two well known US bounty hunting law firms set up offices in the UK, Phillips and Cohen in 2016 and Constantine Cannon LLP in 2017 respectively. Constantine Cannon LLP reportedly tried for years to persuade UK authorities to adopt the US bounty model.

Earlier this year, Forbes reported that Constantine Cannon had teamed up with the organisation Whistleblowers UK. The same article discussed the possibility that a ‘billionaire whistleblower’ will result from the bounty schemes.

There have been multi-billion claims under the FCA. In July this year, Mary Inman of the bounty hunting law firm Constantine Cannon reported on a pending case of $5b healthcare fraud. So, working on a 30 percent bounty, it is theoretically possible for the False Claims Act system to issue a reward of over a billion dollars.

In a parliamentary debate about the finance sector on 18 January 2018 Norman Lamb MP, who secured the debate, called twice for the adoption of US style bounties:

|

Debate on RBS Global Restructuring Group and SMEs 18 January 2018 ‘The truth is that whistleblowers have no real protection in this country. Contrast that with the situation in the United States, where the Dodd-Frank legislation introduced the Office of the Whistleblower, which is there to protect whistleblowers. Whistleblowers are rewarded financially for doing the right thing—they are awarded between 10% and 30% of the sanction collected against the firm, which can run into millions of dollars. What a contrast with the position in this country! We need our own office of the whistleblower, and whistleblowers should be guaranteed anonymity; they should be rewarded for their bravery. Maintaining the integrity of the banking system is of fundamental importance to all of us, and whistleblowers are necessary for that purpose. … The Minister has not yet mentioned the role of whistleblowers. Does he agree that they are vital to maintaining the integrity of the financial system, that they need proper protection—an office of the whistleblower—and that they should be rewarded for being brave enough to reveal wrongdoing?”

|

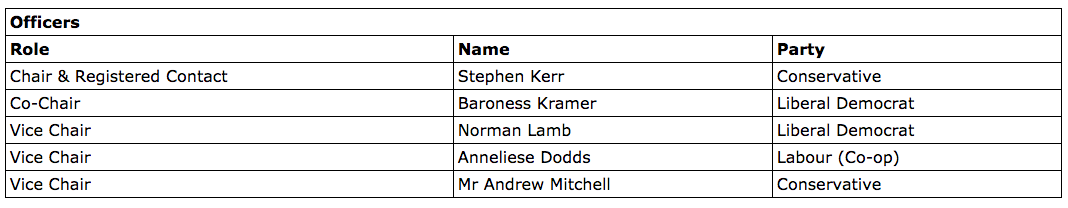

A new whistleblowing All Party Parliamentary Group on whistleblowing was established over the summer. Its officers and full details of its secretariat were revealed on 29 August 2018.

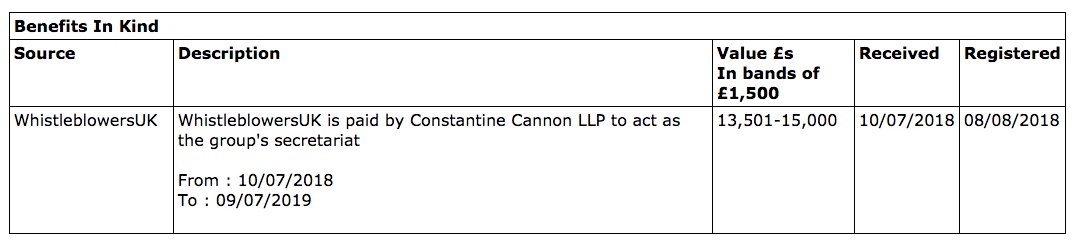

Of great interest to whistleblowers, it became evident that Constantine Cannon had paid Whistleblowers UK to act as the APPG secretariat:

Whistleblowers UK is the trading name of a private company WhistleblowersUK Company number 09347927. (This is not to be confused with the original organisation Whistleblowers UK Company number 08112953, which was dissolved in 2015)

The CEO of Whistleblowers UK and her husband established two new whistleblowing companies in May 2018, Whistleblower Legal Limited and Whistleblowers International Limited.

Whistleblowers UK has advocated for whistleblower rewards:

I asked Whistleblowers UK for details of any disclosable donations under parliamentary APPG secretariat rules, and whether the organisation had received any other remuneration from law firms with an interest in bounty hunting. The Chair of Whistleblowers UK has advised that there were no disclosable donations, but there was no response on the wider question of other remuneration: Correspondence with Whistleblowers UK

Corporate funding for APPGs has been a controversial matter, as there is concern about the access that APPGs may provide to parliament and to ministers.

On 29 August when details of the new whistleblowing APPG were revealed, The Times ran a piece about the APPG, Whistleblowers UK and Constantine Cannon. The banner photograph was of bereaved families from the Gosport scandal about unnatural opiate related deaths, where whistleblowers first raised the alarm in 1991 but were ignored. It was eye catching, but this is precisely the sort of disaster that will not fit easily into bounty hunting schemes.

Whatever one makes of the new whistleblowing APPG, and despite Norman Lamb’s proposal to import the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s Dodd-Frank programme, the known facts about the programme are not compelling evidence of ethical governance.

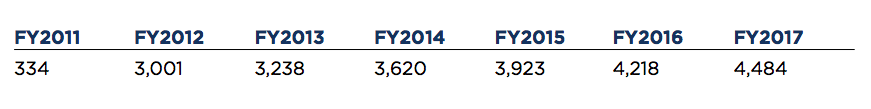

SEC’s Dodd-Frank bounty programme commenced in 2011 and it invites disclosures from both employees and other sources. Tip offs to SEC have increased steadily since the programme’s inception:

Tipsters may qualify for a bounty of up to 30% if their intelligence contributes to government enforcement action that generates more than $1million in fines.

In its 2017 annual report, SEC advised that its bounty programme has resulted in over $975million fines and over $671million in ‘disgorgement of ill-gotten gains and interest’. The programme has paid out a total of $160million in bounties to 46 individuals since inception. However, the Commission has been criticised for welching on its bounty deals and attempting to conceal this. In 2015, the Wall Street Journal obtained data which showed that 247 of 297 (83%) claims for bounties since 2011 had not received a decision from SEC.

Moreover, SEC prosecutes hundreds of enforcement actions every year:

but since the inception of its whistleblower programme in 2011 the Commission has undertaken only three enforcement actions for whistleblower retaliation under the Dodd-Frank provisions.

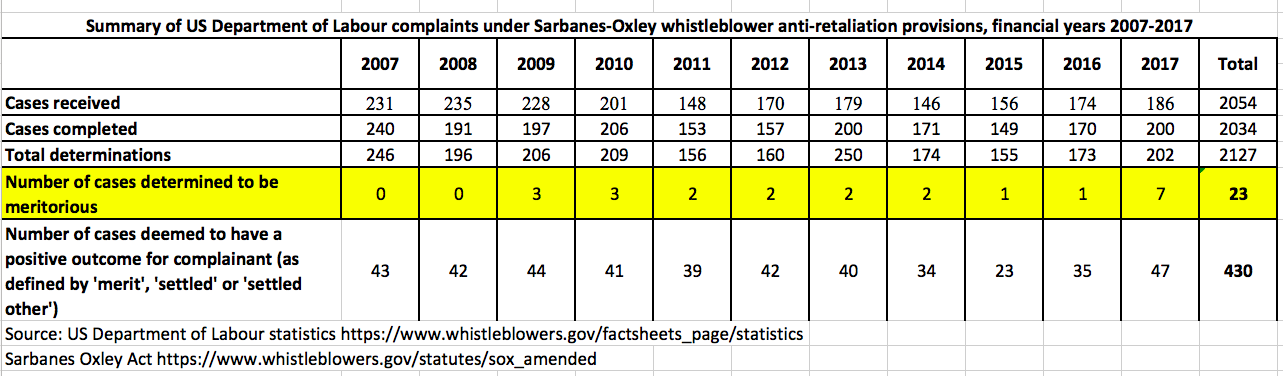

It also appears from government data that US financial sector whistleblowers fare poorly when they apply to the US Department of Labour for administrative remedies for reprisal.

The system is very complicated, but two important statutes under which US finance whistleblowers can file complaints are Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank.

Department of Labour statistics show that between 2007 and 2017, out of 2054 cases received under the Sarbanes-Oxley administrative procedures, only 23 (1%) resulted in a clear win and finding of merit for whistleblowers. About a fifth of Sarbane-Oxley retaliation cases resulted in some sort of positive outcome, even if short of a clear finding of merit.

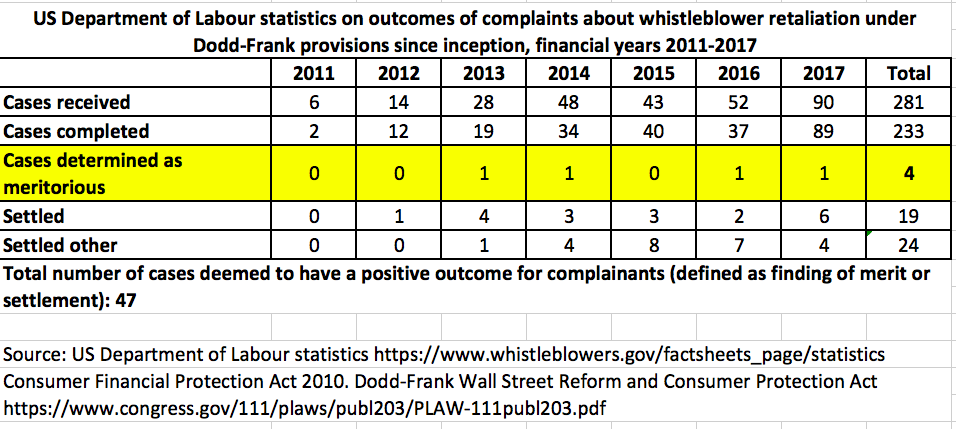

Since the Dodd-Frank administrative procedures for whistleblower retaliation commenced in 2011, only 4 out of 281 (1.4%) complaints received resulted in a finding of merit. Less than a tenth of Dodd-Frank retaliation cases were considered to have a positive outcome for whistleblowers, in terms either of a clear finding of merit or settlement.

Under Dodd-Frank some whistleblowers may be permitted to litigate after exhausting the administrative process for retaliation. There is no complete data on how they fare when they seek legal remedies for retaliation in the courts, but anecdotal reports have highlighted problems with how the law is interpreted, pro-employer bias and issues of jurisdiction. Most recently, SEC issued this discouraging clarification:

“On February 21, 2018, the United States Supreme Court issued an opinion in Digital Realty Trust, Inc. v. Somers stating that the Dodd-Frank anti-retaliation provisions only extend to those persons who provide information relating to a violation of the securities laws to the SEC. To understand how this may affect you, we encourage you to consult with an attorney.”

As with the FCA, tip offs to SEC’s Dodd-Frank programme can be made from outside of US territory. In the Commission’s 2017 annual report, the UK led the field in that year with 84 tip offs, followed by Canada (73) and Australia (48).

Some may feel that the finance sector needs special arrangements for whistleblowing, for the greater good and in consideration of serious disruption to public services and misery that can be inflicted on millions of people from major financial disasters. But the Bank of England is very much opposed to bounties. Whilst some of the BoE’s observations about the effectiveness of bounty models in generating tip offs have been disputed, its general points about the ethical problems with bounties are well made. That said, the BoE’s limp offering of culture change is unacceptable:

“Our aim will be to ensure that the culture in firms is one where people are prepared to speak up, as part of improving behaviour throughout the firm.”

This mirrors the political line and tokenistic measures that the Westminster government has put in place for the NHS.

Neither the extremes of wilful blindness and impunity for retaliators, nor pitiless monetisation of whistleblowing which treats many whistleblowers as disposable, are acceptable. What is needed is seriously implemented protection for all genuine whistleblowers.

When Norman Lamb vice chair of the new whistleblowing APPG, was in power as a minister at BIS in 2012, he made some similar arguments to those made by the Bank of England in rejecting bounties. He warned of the inadvisability of mixing governance up with personal enrichment, the need to discourage “speculative” claims and to prevent speculative claims from harming genuine whistleblowers through disrepute:

|

Debate on Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Bill 3 July 2012 ‘There have been calls to make the penalty payable to the individual, but I would strongly resist that. The measure is intended to benefit all employees by encouraging employers to behave better. That is addressed only at those employers that fall below the standards that any decent person would expect. The measure is not intended to benefit individual claimants directly. The only effect of such a step would be to incentivise employees to bring speculative claims—the very opposite of the steps that we are taking to deal with concerns about weak claims. The employee gains nothing from a decision that an employer has behaved particularly badly in an individual case. They get the compensation for the loss that they have suffered, as I have explained. … To return to my explanation of the purpose of the clause and of why the Government have designed it in such a way, the decision in the case of Parkins v Sodexho Ltd has resulted in a fundamental change in how the Public Interest Disclosure Act operates and has widened its scope beyond what was originally intended….The ruling has left the Public Interest Disclosure Act open to abuse and is creating a level of uncertainty for business. Concerns have been expressed, underpinned by anecdotal evidence, which I appreciate is a dangerous word to use in this Committee, from lawyers—that is an even more dangerous word—that it is now common practice to encourage an individual to include a Public Interest Disclosure Act claim when making a claim at an employment tribunal, regardless of there being any public interest at stake. That has a negative effect on businesses, which face spending time preparing to deal unnecessarily with claims that lack a genuine public interest element. It also has a negative effect on genuine whistleblowers, by encouraging speculative claims.’

|

Protecting whistleblowers will never be easy. Bounty models by definition do not try hard enough to ensure that whistleblower protection is effective: the proffer of large rewards is a tacit acceptance of unacceptable levels of reprisal. It is by design a solution – of sorts – but for just a few. The house plays the numbers.

The bounty model of whistleblowing is a glorified one-armed bandit.

And it’s people who should count the most, not cash.

RELATED ITEMS

- This is Mary Inman of the US law firm Constantine Cannon speaking about whistleblowing bounties and qui tam suits at the Byline festival on 24 August 2018:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=QoY6FEEeTNI

Inman argued that the use of paid informants is an accepted technique of law enforcement.

- In recent debates, there has been conflation of compromise agreements with ‘bounties’ and ‘bribes’. For example:

Such statements imply that whistleblowers accept cash to keep quiet against the public interest. The reality is much more complex. Gags unquestionably do discourage some staff from speaking out, but many compromise agreements are implemented after a long battle, and after patient safety disclosures have been made. The clue is the name : compromise agreements are usually substandard and do not even compensate fairly for all serious loss. They quite often leave whistleblowers in chronic economic insecurity. From whistleblowers’ perspectives, settling may be a means of limiting litigation risk when there are mouths to feed, families to protect from the stress of endless disputes or self care when health has been seriously affected. What compromise agreements quite often hide are embarrassing details of what employers do to whistleblowers, as opposed to the whistleblower’s original concerns. So in short, it is mostly victimisation and attrition that leads to compromise agreements. To equate this with ‘bounties’ or being ‘rewarded’ is not a serious argument.

- There is an APPG on banking of which Norman Lamb is Co-Chair.

The papers for this APPG show that it was working with the organisation Public Concern at Work (which was just re-branded and is now known as ‘Protect’) and Whistleblowers UK to establish an Office for the Whistleblower:

Some finance sector whistleblowers have expressed concern that this APPG has also accepted industry funding.

UPDATE 12 FEBRUARY 2020

Norman Lamb resigned from the Whistleblowing APPG because he was unable to get answers to questions about finances and probity which I put to the APPG.

Norman Lamb MP has resigned from the Whistleblowing All Party Parliamentary Group

The Whistleblowing APPG brought out a new Bill in January 2020 to establish an Office For the Whistleblower which contains no commitment to protecting whistleblowers, ensuring that their concerns are properly handled nor robustly deterring reprisal. But it does specify items which would be beneficial to whistleblowing industry middlemen.

$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$

Thank you for all of the background research and information and for organising its presentation so intelligibly.

The business of America is business.

Everything can, and will be, monetised.

No other game in town and, of course, Brits will join in.

Not a matter of right or wrong, lawful or unlawful, just or unjust, decency or suffering – it’s all about doing deals and monetising.

Eileen Chubb expresses my views more eloquently than I can – unacceptable situations to be remedied with procedures put in place to ensure no repeat offences, those responsible to be held accountable and for serious events, prison sentences. Whistleblowers shouldn’t be left out of pocket or, more accurately destitute with their futures and reputations smashed, but neither should they be ‘rewarded’ as if they were prostitutes – what an insult.

However, without a huge platform, insufficient people will hear or listen. Thus we rely on our elected representatives and hope that they can resist the siren call of big money and cheap headlines and instead listen to experts like yourself and Eileen and put practical and effective procedures in place to protect the vulnerable and promote decency.

Thank you and kindest regards.

LikeLike

Not a matter of right or wrong, lawful or unlawful, just or unjust, decency or suffering – it’s all about doing deals and monetising.

How right you are zara. You only have to sit in the claimants waiting room in a tribunal for a few minutes to see the UK have more than our fare share of “bounty hunters” doing deals with the other side in WB cases. Those deals ignore the reasons why they are there in the first place and involve getting their costs paid as a priority!

We are very PC in the UK so we call these people employment lawyers.

LikeLiked by 1 person