By Dr Minh Alexander retired consultant psychiatrist 13 June 2023

Background

The private company the Good Governance Institute (GGI) sells consultancy services and has many links with the NHS. It lists a large group of current and former NHS managers and NHS regulatory staff amongst what it calls its “people”.

What this designation signifies seems vague.

Jacqui Smith the controversial former Home Secretary, former Chair of University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (UHB) and current chair of Barts Healthcare NHS Trust and Barking Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust is listed amongst the Institute’s “people”.

Upon a FOI request to Barts, Smith denied that this amounted to any specific role: “Rt Hon Jacqui Smith has no formal board or management title or any ongoing role with GGI” but nonetheless Smith is listed as one of the GGI’s “people”.

Several other UHB managers are listed as GGI “people”.

The GGI carried out a “Well Led” review on UHB in 2019, but more on that another time.

Moreover, the GGI is known for the fact that it hired Mason Fitzgerald former NHS trust director despite his sacking by the NHS after a false claim about his qualifications.

The Good Governance Institute at Sussex

What I cover here is a link between the GGI and University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust, where it was revealed at the Employment Tribunal on 5 June 2023 that the police are investigating allegations that may amount to gross negligence manslaughter.

The Guardian reported that Mr Krish Singh, surgeon, one of the Sussex whistleblowers had raised concerns about corporate actions which resulted in deaths:

“Singh claimed the trust had promoted insufficiently competent surgeons and overused insufficiently skilled locums.”

“…he claimed that cost-saving changes at the hospital “were driven through that were grossly unsafe and ultimately drove up complication rates and patient mortality”.

Another senior trust whistleblower Mr Mansoor Foroughi, surgeon, raised similar concerns.

University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust was formed by the 2021 merger of Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, a regulatory and political favourite run by Marianne Griffiths CEO and George Findlay Medical Director, with the struggling trust Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust.

From April 2017 onwards Marianne Griffiths became CEO for BSUH as well.

BSUH remained a PR thorn in Griffith’s side for the next two years, with BSUH stuck in special measures until 2019. when it was taken out of special measures by the Care Quality Commission and jumped from a rating of “inadequate” to “good”.

In the CQC’s evidence appendix for the related inspection report, CQC stated that the trust had hired the Good Governance Institute and ensured a “golden thread” of quality throughout its improvement strategy:

“Governance

The chief medical officer explained that when the current executive management team had taken over the management contract for the trust, they felt concerned about the governance and assurance arrangements in place and felt they did not have assurance about the quality of treatment and care being provided for patients. They found examples of good clinical governance and reporting in place at a service level, but this information was not being reported up to the board. The trust had therefore commissioned an external review of the governance arrangements from the Good Governance Institute.

Because of this review, a structure of five divisions was put in place where previously there had been 13 directorates. The divisional structure led by a triumvirate of a clinical director, general manager and head of nursing had provided the building blocks for the revised governance arrangements. The Good Governance Institute provided training in governance for these leaders. the non-executive directors and executive directors described the journey for the triumvirate leaders moving from a concern that more reporting was going to be required of them, to understanding governance and how the data and reporting would enable them to drive quality improvement.

The board invited the Good Governance Institute to carry out a review of the trust’s quality governance structures, which resulted in 31 separate recommendations being made. The trust acted to address these issues and the Good Governance institute carried out a further review reporting on progress against these actions. A focus of this work has been to strengthen quality governance arrangements at divisional level.

The trust had effective structures, systems and processes in place to support the delivery of its strategy including sub-board committees, divisional committees, team meetings and senior managers. Leaders regularly reviewed these structures. The trust reported regularly through its governance arrangements on progress against delivery of its strategy to the board, trust executive committee and to other relevant committees. However, the structure needed more time to become fully embedded.

In interviews with the chair of the Quality Assurance Committee, the chair of audit and the chief medical officer (the executive officer responsible for governance), all non-executive and executive directors were able to describe the governance structure and how it functioned.

The effectiveness of the governance arrangements was observed on inspection at Strategy Deployment Review meetings. Each of the three leaders of each division owned and presented the data for their breakthrough objectives. They had interrogated the data to find root causes where the objectives were behind plan and had devised action plans based on this knowledge to bring the objective back on track.

The Chair of the Audit Committee explained that under the previous administration, assurance was not provided through reporting and they were not getting the information they needed. The new structures provided a joined-up approach that provided assurance on quality and delivery against the Patient First Strategy and breakthrough objectives and delivered quality improvement.

Quality was a ‘golden thread’ running through the trust Patient First Strategy. In all the interviews undertaken on inspection the golden thread of quality was evident in the use of data both quantitative and qualitative and how this was triangulated and reported through the Quality Steering Group to the Quality Assurance Committee and the trust board.

Non-executive and executive directors were clear about their areas of responsibility. Performance against the trust’s patient first strategy, true north and breakthrough objectives was focused and reinforced through the trust’s strategic deployment review approach. There was clear ward to board line of sight through daily performance huddles, weekly driver meetings, Divisional Strategy Deployment Review, executive level Strategy Deployment Review and the board.

The Chair of the Quality Assurance Committee gave an example of challenge and holding the executive directors to account when an action plan did not evidence sufficient learning to drive improvement and required further work to be undertaken.

The quality dashboard was aligned to the quality priorities along with the quality improvement plan with actions being taken and monitored at divisional, corporate and board level through the quality governance system, Quality Assurance Committee and board. The Audit Committee evaluated the effectiveness of the trust’s structures and processes in relation to the management of risk, the management of performance and financial management and the management of quality and quality improvement.”

Well, if your quality dashboard looks good, what could possibly go wrong?

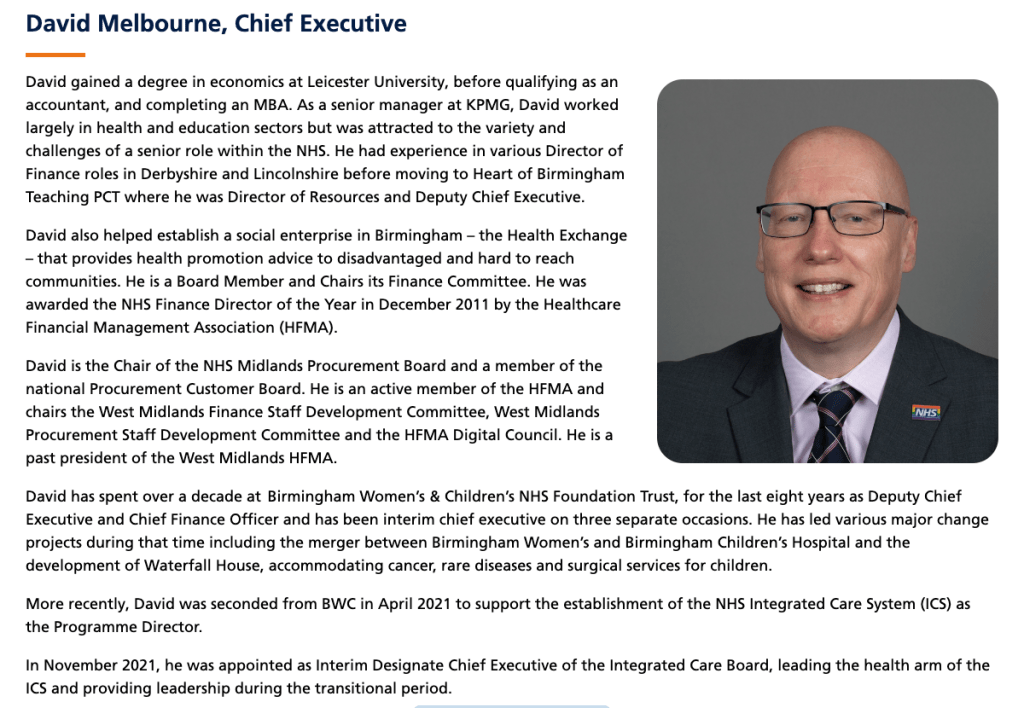

And who led the CQC inspection team that concluded BSUH should be taken out of special measures? The inspection team was led by Cath Campbell now CQC Deputy Director of Operations and a David Melbourne.

Would that be the David Melbourne who was then deputy chief executive of

Deputy Chief Executive of Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust and is now the much-criticised CEO of Birmingham and Solihull ICB, a body that has helped to protect failing UHB executives and to obfuscate the reality at UHB?

Just fourteen months after the remarkable January 2019 CQC inspection report praising Griffiths et al, Health Education England noted horrendous governance and serious patient safety failings at the trust.

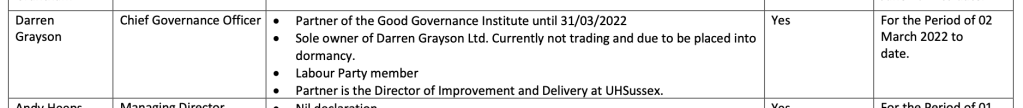

Darren Grayson formerly of the Good Governance Institute, now a University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust director

I am informed that the Good Governance Institute’s review of BSUH in 2018 was led by Darren Grayson, executive director and partner at the Good Governance Institute 2016-2022.

The Good Governance Institute later celebrated its work at Sussex with a little blog:

And then what happened next?

In March 2022 Griffiths appointed Darren Grayson, executive director and partner of the Good Governance Institute, on to the board of the newly formed University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust as Chief Governance Officer.

This is Grayson’s LinkedIn entry, which gives some of his CV in terms of past NHS posts prior to becoming an executive partner at the GGI. He was a local NHS executive, previously working as CEO of NHS Brighton and Hove, and then CEO of East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust.

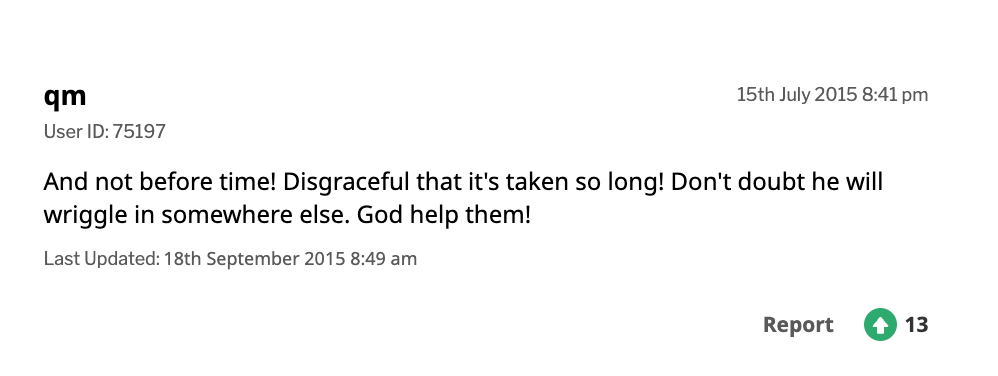

Notably, Grayson stood down from his post as CEO at East Sussex Healthcare NHS trust in 2015, after a CQC inspection of the trust rated it as “Inadequate” both overall and on the “Well Led” domain.

The CQC found evidence of managerial bullying and other signs of poor culture. For example:

“The themes identified related to the quality of staff engagement, low morale, and a bullying and harassment culture from senior management.”

“The trust board continues to state they recognise that staff engagement is an area of concern but the evidence we found suggests there is a void between the Board perception and the reality of working at the trust. At senior management and executive level the trust managers spoke entirely positively and said the majority of staff were ‘on board’, blaming just a few dissenters for the negative comments that we received.

We found the widespread disconnect between the trust board and its staff persisted. This is reflected in the national NHS Staff survey.

….The trust told us they were disappointed by the results; but we saw no direct programme to address this or to change the position. There remained a poor relationship between the board and some key community stakeholders. We found the board lacked a credible strategy for effective engagement to improve relationships.

….Within the trust, we did not see a cycle of improvement and learning based on the outcome of either risk or incidents.

• Staff remained unconvinced of the benefit of incident reporting, and were therefore not reporting incidents or near misses to the trust. the trust was not able to benefit from any learning from these. this position had not improved.

• The risk register was not capturing risks in a robust way.

• We saw a redesign of the governance structure, but were unable to yet see any significant benefits or improvements from this.”

A special meeting of the local Joint Health Scrutiny and Overview committee reached a unanimous vote of no confidence in him:

No confidence in NHS Trust bosses

The Chair of the Committee commented: “You are the captain of the ship which has hit rocks, and it is starting to sink and I think the biggest morale boost you can give to staff is to say sorry and then offer your resignation.”

Grayson reportedly refused to resign initially but later stepped down:

Controversial NHS boss to stand down – but chairman to remain in position

Local MPs called for Grayson’s resignation.

The unions also called for his resignation and warned against any golden handshake.

“The CEO did not listen to his own staff, public opinion or GMB. Instead he openly criticised and blamed those, including GMB, for challenging him and his management style.”

This is Grayson’s biography from the University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust’s website, which adds political detail in terms of his work at the New Labour hub, the No 10 delivery unit which ran 2001-2005.

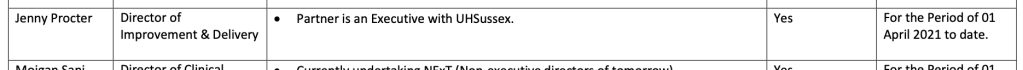

Importantly, Darren Grayson’s partner is Jenny Procter, another director at University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust, as revealed by trust declarations of interest:

According to her LinkedIn entry, Procter has been the trust’s Director of Improvement & Delivery since April 2021, and before that she was Director of Efficiency & Delivery from 2017 to 2021 for both its predecessor trusts.

Matters arising

So, what does it say about Marianne Griffiths’ leadership of University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust that she hired someone like Darren Grayson to review trust governance and then later gave him an executive job, after such a disaster at East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust?

Ironically for Griffiths et al, their enterprise with the Good Governance Institute may well tip the balance in any consideration of corporate failures in the deaths scandal. In the

BSUH quality accounts of 2017/18, Griffiths claimed:

“At a corporate level, we are working with Good Governance Institute to ensure clear lines of sight from the front line of service delivery through to board level on quality and safety. This means that we can identify – and resolve – issues much earlier, contributing to the improvements in patient care.”

As above, the CQC later reported that the “clear line of sight” by the trust board was in place in its January 2019 inspection report. This appears to be additional evidence supporting staff disclosures to Health Education England that the board, through Griffiths, knew about the deaths, staff concerns and lack of governance in the surgical division.

I am requesting copies of all Good Governance Institute reports undertaken for the trust under FOIA.

I will also ask CQC to confirm that David Melbourne was an employee of the CQC as an inspection chair/ executive reviewer, to disclose whether this continues and to disclose whether any other executives from UHB and Birmingham and Solihull ICB are CQC executive reviewers.

CQC’s unseemly habit of employing part time/ bank staff from regulated bodies, especially at director level, has long been a source of conflicted interests and incestuousness which has undermined the authority and legitimacy of its inspections.

Is there a ‘club culture’ at the heart of the NHS’s quality regulator?

UPDATE 23 SEPTEMBER 2023

The Times has picked up the story about Darren Grayson’s recycling to the Sussex board as Chief Governance Officer:

Surgery deaths continued after repeated warnings by coroners

Importantly, it has now been made public that shockingly, Grayson is the trust’s police liaison for Sussex police with respect to the polic investigation into police deaths.

This is despite the fact that there are questions of conflict of interest from his review of trust services in his previous capacity as a consultant for the so-called Good Governance Institute. The GGI was investigated by BBC Newsnight.

RELATED ITEMS

This is a published CIPFA profile of David Melbourne in question and answer format, from when he was CFO at Birmingham Women and Childrens, in which Melbourne sympathises with the poor and emphasises the importance of staying true to your values.

David Melbourne, Chief Finance Officer

This is Birmingham and Solihull ICB’s biography of Melbourne:

Melbourne took part in a charade in which the ICB and UHB misled the public and partner agencies by claiming that David Rosser the former CEO of UHB stepped down, when he in fact remained employed by UHB:

NHSE, ICB and UHB’s three-ring circus and Rosser’s digital assignment

The neglected Kark review on unfit NHS managers

The Kark review, commissioned by Steve Barclay five years ago made a string of recommendations for preventing the recycling of unfit managers in the NHS. The task of implementation was given to NHS England, which is notorious for running the so-called “donkey sanctuary” for failed senior NHS managers. There has been no sign yet of any implementation, and NHS England claims that Steve Barclay himself dropped Kark’s recommendation for a disbarring mechanism. Correspondence to Mr Barclay about the failure to implement Kark’s recommendations has so far gone unanswered.

I leave readers with this comment below The Brighton Argus report on Grayson’s fall in 2015, by a perspicacious member of the public:

The NHS National Freedom To Speak Up Guardian helped Griffiths and co by disadvantaging trust whistleblowers in 2018, when she delayed a review of whistleblowing governance. This aspect of the saga can be found here:

A Study in Delay: The National Guardian & Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust

I have asked the CQC to investigate the National Guardian’s Office’s handling of whistleblowing matters at Sussex.

A prime example of the fate of whistleblowers at UHB, another NHS trust which favoured the GGI, can be found here:

Mr Tristan Reuser’s whistleblowing case: Scandalous employer and regulatory behaviour on FPPR

The twists and turns at Sussex illustrate very well what an insurmountable and well constructed wall NHS whistleblowers often face.

Thank you for a rivetting read.

I wonder if I’m right in thinking that the Good Governance Institute was inspired by the Good Housekeeping Institute? But, the latter undertake useful work.

Anyway, I read through the relevant list of characters, and part of me is glad that they are at least employed – as opposed to having to forlornly wander the streets searching for warmth and shelter – but I am still concerned for the victims of inadequacy, i.e. the whistleblowers and harmed patients. If only there were an official body dedicated to looking after them.

LikeLike