By Dr Minh Alexander NHS whistleblower and former consultant psychiatrist, 11 December 2018

Summary: Whilst we wait for publication of the delayed Kark Review into CQC’s appalling handling of Regulation 5 Fit and Proper Persons (FPPR), I focus in detail on the fact that failure to investigate or properly investigate whistleblowers’ concerns is an act of detriment.

The Employment Tribunal concluded in the whistleblowing case of disgraced former trust chief executive Paula Vasco-Knight, that her trust South Devon Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, had repeatedly acted dishonestly in its investigation into the concerns of two whistleblowers.

Relevant details from the judgment are set out below.

The unanimous judgment of the ET panel was that South Devon’s failure to conduct a fair investigation into the whistleblowers’ concerns constituted a “significant” act of detriment:

The CQC compounded this victimisation through its protection of Paula Vasco-Knight and through in its poor handling of FPPR, which helped to whitewash the trust’s dishonesty.

The whole saga illustrates how so-called independent whistleblowing investigations commissioned by employers can be easily manipulated.

And yet Robert Francis in his report of the Freedom To Speak Up Review expressly recommended that such “independent” investigations should remain the mechanism for investigating disputed issues, and he pretended that this was safe. This was despite the fact that Francis was aware of the South Devon/ Vasco-Knight case and had previously condemned it as an example of “oppressive managerial behaviour”.

At present, the Department of Health and Social Care, Robert Francis and CQC are being pressed about CQC’s longstanding, unsupportable refusal to investigate whistleblower’s concerns. Healthwatch England and CQC have both apologised for Francis’ silence, but still no answer is forthcoming. The DHSC has given initial indication that CQC has the power to investigate. Further liaison continues.

South Devon Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust’s dishonest handling of the investigation into whistleblowers’ concerns

Clare Sardari and Penny Gates raised concerns about nepotism by Vasco-Knight whom they believed had improperly favoured and employed Nick Schenk, who was the boyfriend of Tahnee, Vasco-Knight’s daughter, without declaring an interest.

They were supported in their concerns by Anthony Farnsworth chief executive of Torbay and Southern Devon Health and Care NHS Trust, which was the whistleblowers’ primary employer.

The Employment Tribunal found that the whistleblowers were threatened by Adrienne Murphy the Director of Workforce and Organisational Development who said words to the effect that they would be “immediately sacked” if they pursued their concerns (para 28).

CQC also rejected an FPPR referral on Murphy, who is now a director at Cornwall Partnership NHS Foundation Trust.

According to the ET, Murphy tried to dissuade Peter Hildrew the chair of South Devon Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust from instigating an investigation into the whistleblowers’ concerns:

Hildrew commissioned the investigation, with agreement from Torbay and Southern Devon Health and Care NHS Trust, but he removed Nick Schenk from the list of witnesses:

Within a day of each other, Nick Schenk and Vasco-Knight’s daughter Tahnee wrote to Hildrew claiming that their romantic relationship had not started until after Schenk had been given a job by Vasco-Knight’s trust:

The ET noted that Hildrew failed to disclose these letters to the whistleblowers:

The ET noted that Hildrew initially denied having any input into drafting the investigation report but admitted under cross examination that he had sight of and commented on a draft investigation report:

The investigation report nevertheless concluded that Vasco-Knight’s behaviour required further examination as regards adherence to the NHS managers’ code of conduct.

The ET noted that Vasco-Knight’s trust tried to dishonestly conceal this finding:

Under FPPR, a trust director should not be “party” to serious misconduct.

It seems hard to believe that Vasco-Knight was not party to South Devon’s mishandling of the investigation of the two whistleblowers’ concerns. This is especially as according to the ET judgment, Vasco-Knight’s trade union representative made representations on her behalf that the investigation report should not be shared with the whistleblowers’ primary employer, Torbay and Southern Devon Health and Care NHS Trust:

Vasco-Knight’s trust misled Torbay and Southern Devon Health and Care NHS Trust by misrepresenting the contents of the investigation report:

Vasco-Knight’s trust chair, Hildrew, wrote thus to the two whistleblowers:

Vasco-Knight maintained a narrative that she had she had been unfairly accused, and went as far as implying that the whistleblowers were racially biased against her:

The ET found that Vasco-Knight was instrumental in refusing to allow the whistleblowers back to work at her trust. They were seen as “vexatious”.

The CQC and whistleblowers’ concerns

It is breathtaking that Mike Richards, former CQC Chief Inspector of Hospitals, Rebecca Lloyd Jones CQC Head of Legal Services et al turned their backs on this damning trail of deliberate wrongdoing, and quietly shut down the FPPR referral on Vasco-Knight without even informing me, the referrer. This allowed her to be promoted to chief executive at St Georges without fuss and opposition.

But it is perhaps worth remembering this revealing passage from a Manchester Business School evaluation of the CQC:

“To recruit external inspectors or inspection chairs, senior CQC staff had used professional contacts and formal and informal networks (such as royal college affiliations) predominantly, rather than the open recruitment advertising process. One interviewee claimed that ‘my recruitment process was Mike Richards badgering me until I said yes’ (Doctor, CQC inspection team).”

Club culture is part of why CQC has failed to do its duty under FPPR, and why it has belittled and minimised whistleblowers’ concerns about poor whistleblowing governance by unfit managers.

This is consistent with CQC’s fierce refusal these last nine years since it was established, as a neutered alternative to predecessor health regulators who had embarrassed ministers, to investigate individual whistleblowers’ disclosures about poor care.

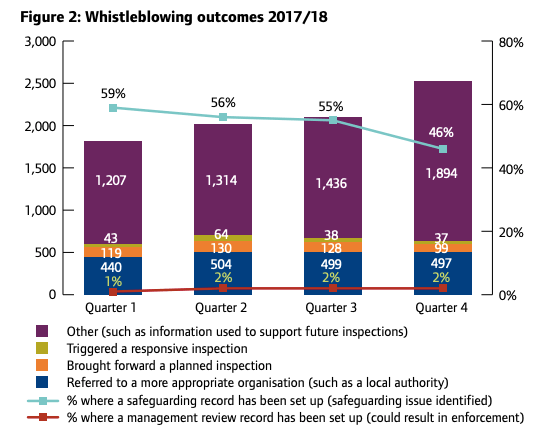

CQC has increasingly shoved whistleblowers’ disclosures in a drawer. In the last few years it dealt with about half of disclosures in this manner. But worryingly, CQC’s latest 2017/18 annual report shows that the majority of disclosures are now long grassed as no ‘further action’ or ‘filed as information for a future inspection’, as shown in the purple ‘Other’ category in this bar chart:

CQC pretends that “something is done” by occasionally ringing up trusts, claiming that inspections are brought forward as a result of disclosures or passing the disclosures to other agencies. But it simply will not do what matters most: investigate.

Recently, CQC told me that it would be reviewing this policy of not investigating whistleblowers’ disclosures, and by implication admitted that it might have got it wrong all along.

Robert Francis concluded in his report of the Freedom To Speak Up Review of February 2015 that all system regulators currently have the power to investigate whistleblowers’ concerns.

|

“All the systems regulators who are prescribed persons can take action to investigate the issues in any protected disclosure made directly to them” Page 19 Freedom To Speak Up Review

|

Francis didn’t seem to have done much about this as a CQC NED, because after his Review report was published, CQC continued to merrily insist that it could not investigate individual whistleblowers’ concerns. I wrote to him on 24 October 2018 as Chair of Healthwatch, and therefore a member of the CQC board, and have chased subsequently. Both CQC and Healthwatch England have apologised for the lack of response, but there has still been no reply.

In the meantime, CQC shared revised guidance for its inspectors on whistleblowing matters. The section on how to respond to whistleblowers contains no instruction to investigate whistleblowers’ concerns.

I also raised the issue with the Department of Health and asked it to either confirm that CQC has the power to investigate whistleblowers’ concerns, or to change CQC’s regulations to make this unequivocally so.

So far, the DHSC seems to believe that this passage from the government’s response to the Gosport Independent Panel’s report on the Gosport deaths disaster is confirmation that CQC has the necessary power to investigate whistleblowers’ concerns when appropriate:

“2.16 All whistleblowing concerns raised with the CQC are forwarded to the local inspector for consideration. This allows the CQC to spot problems or concerns in local services that it may need to act upon.”

I have asked the DHSC for clarification and confirmation that this is definitely so, and have suggested that if the DHSC’s intention is that CQC should investigate whistleblowers’ concerns, it should straighten things out with its miscreant regulator.

Else, we shall continue with more State abuse of Health and Social Care whistleblowers’ human rights, added detriment inflicted by the regulator that is supposed to uphold values and standards and betrayal of the public interest.

What is really needed is statutory compulsion of the proper handling and investigation of whistleblowers’ concerns, as part of substantive reform of currently unfit UK whistleblowing law.

UPDATE 26 DECEMBER 2018

In a report published on 19 December 2018, PHSO have partially upheld a complaint about CQC’s serious mishandling of the FPPR referral on Paula Vasco-Knight.

CQC has disgraced itself by wriggling against even PHSO’s partial finding.

The events, with correspondence to the Secretary of State, are summarised here:

CQC’s Victimisation of Whistleblowers: Failure to Investigate Concerns

RELATED ITEMS

What could a new whistleblowing law look like? A discussion document

Witness statements about concerns at Gosport War Memorial Hospital

The Disinterested National Guardian & Robert Francis’ Unworkable Freedom To Speak Up Project

Thank you for recording for posterity the evidence as opposed to the P.R.

The first rule for a bureaucracy is to protect the bureaucracy (and the salaries of the elite thereof) notwithstanding any duties relevant to the purpose of the bureaucracy or any innocents mangled up in its limitations.

LikeLike