By Dr Minh Alexander, NHS whistleblower and former consultant psychiatrist, 8 October 2018

|

Summary: Protect, formerly known as Public Concern at Work (PCaW), is the dominant UK whistleblowing charity. It played a large part in introducing very ineffective UK whistleblowing legislation twenty years ago. Whilst this was probably done with good intentions, the charity has not redeemed the mistakes of the past by calling for replacement of the law or urgent correction of the law’s most serious deficits. For twenty years, UK whistleblowing law has not compelled anyone to investigate whistleblowers’ concerns. Protect is an important reservoir of specialist knowledge because of its dominance of the market. It receives substantial income from the public purse but has declined to reveal full details of this income. It provides services to employees and employers. Some may be concerned about the potential for divided loyalties, priorities and the degree to which Protect challenges power. In any case, the charity has no official status and no powers to protect whistleblowers. The charity has not challenged the most obvious frailties of sham government whistleblowing policy. The Freedom To Speak Up project, which is arguably the biggest block to real reform, not only goes unchallenged but was this week endorsed by a Protect trustee. In the terrible shadow of the Gosport disaster, the public has a powerful need for a statutory, independent expert body with powers to protect whistleblowers and the public interest, and is subject to proper legal accountability.

|

The UK whistleblowing scene is a rubble strewn landscape.

Defective UK whistleblowing legislation, the Public Interest Disclosure Act, (PIDA) has been in force for twenty years. It gives workers the notion that they are protected, until it is too late and they realise they are not.

The law is so bad, it is turned against whistleblowers as a weapon.

Successive waves of bewildered whistleblowers have discovered that UK law is disinterested in the content of their concerns.

Deaths due to poor whistleblowing governance have continued since PIDA came into force. For example, at MidStaffs, in the case of Ian Paterson the rogue surgeon and at Liverpool Community Health NHS Trust.

Opinions vary about whether it is better to have a bad law rather than none at all.

Lord Touhig who proposed a close precursor of the current legislation commented:

Richard Shepherd MP the proposer of the current legislation reportedly defended its honour somewhat hotly:

“Pida is blamed for all sorts of things that aren’t its fault,” he said.”

If Shepherd gave the legislation life, the midwife was the charity Public Concern at Work (PCaw), now re-branded as ‘Protect’. Protect sees itself thus:

From Protect’s 2012 submission to Transparency International

From Protect’s 2012 submission to Transparency International

Protect promised much of PIDA, which has not come to pass. For example, PIDA has not delivered accountability as originally promised:

“We warmly welcome this Bill. It will give employees the assurance to sound the alarm on abuse in care, fraud and other serious malpractice and it will provide employers an incentive to handle such concerns responsibly. As it will ensure that employees and employers are less likely to turn a blind eye to the wider public interest, it will improve both accountability and public confidence in the workplace.” Michael Brindle QC, Public Concern at Work

Since PIDA was passed in 1998 and came into force in 1999, PCaW has dominated the conversation.

Protect has been ubiquitous. Its name appears in the majority of public bodies’ whistleblowing policies as the go to source for independent whistleblowing advice for workers. Few conferences on whistleblowing pass without Protect appearing on the attendance list. It has had a place for years on the national user group for the Employment Tribunal. Twining around any number of working groups, Protect has a well-marked dance card.

Protect has amassed much power as a keeper of secrets. Access to secrets often generates more access, and the organisation is embedded into public life. And in fairness, because it cornered the UK market in whistleblowing, Protect holds vast data and knowledge. It would also be churlish not to acknowledge that some of Protect’s work has been very useful in advancing understanding about whistleblowing matters.

Although it must also be said that the organisation sometimes overlooks sampling limitations. It has sometimes implied that its findings are representative, when they only relate to the sub-group of whistleblowers who have found their way to Protect’s front door. But it may be tempting to overlook data limitations when trying to emphasise one’s importance.

For example, in its ‘Whistleblowing Commission’ report, Protect stated:

“Further cases analysed in “The inside story” revealed that 74% of whistleblowers said they were ignored when they first raised a concern. This research also established that it is likely individuals only raise a concern once (44%) or twice at most (39%) before giving up.”

Strictly speaking it ought to have clearly stated that 74% of whistleblowers who contacted Protect said they were ignored when they first raised a concern. Those who ring the Protect helpline are more likely to have experienced problems with raising concerns. A prospective, whole population study as opposed to a retrospective trawl of Protect helpline case files would likely reveal different, less dramatic findings.

Protect has described itself as a ‘self-funding’ organisation. In 2017 it registered £578K staff costs, and £708K income. The lines between the charity and the government are blurred by the fact that Protect accepts public money by selling services to the public sector. For example, Protect operates an NHS whistleblowing helpline for the Scottish government. It has sold training services to the government’s Freedom To Speak Up Project. Protect also trains staff from government departments. FOI disclosure 12017/11460 of 24 May 2017 by the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, which leads on UK whistleblowing law, indicated that the Department had sent two members of staff on a Protect training course.

|

Protect’s services to the public sector An FOI disclosure by Health Education England revealed that it paid Protect a total of £129K for training services. An FOI disclosure by the Scottish government revealed that it paid Protect £142K for running its whistleblowing helpline between April 2013 and July 2017 There is no comprehensive client data on Protect’s website. Some but not all clients are named. There are also occasional promotional tweets from the charity’s social media account, which reveal some of the organisations to which training services are provided. Last year I asked Protect’s former CEO and colleagues about the charity’s clients and revenue. They advised that they could not tell me, or tell me with any accuracy: – who its 300 plus clients were – who its public sector clients were – its overall income from public sector clients Correspondence with Cathy James former CEO of PCaW et al (now Protect)

|

Protect provides free telephone advice on whistleblowing which is available to all workers. However, it also sells consultancy services to individual employers. Questions have long been asked about the potential for conflict.

Indeed, taking the example of Health Education England (HEE), Protect was simultaneously selling whistleblowing governance services to HEE whilst intervening in the case of Dr Chris Day who was in dispute with HEE, and submitting a third party brief to the Court. Moreover, Dr Day was represented by a trustee of Protect, James Laddie QC.

Protect stated in an annual report of 31 December 2017 that its trustees have the responsibility for ensuring there are no conflicts:

It is not explained how this is achieved.

Protect’s website says the organisation provides the following services to whistleblowers who call its helpline:

This menu would raise substantial hope in any inexperienced whistleblower, searching frantically for safe harbour.

There is little activity and outcome data about Protect’s helpline on its website. Raw contact numbers are given in annual reports. The 2017 report gives the following figures:

Protect tells others how to run their whistleblowing arrangements. Its 2013 ‘Whistleblowing Commission’ put forward a draft code of practice which advised that best practice included regular review of whistleblowing arrangements, which included measuring whistleblower experience:

‘d) conduct periodic audits of the effectiveness of the whistleblowing arrangements, to include at least:

- a record of the number and types of concerns raised and the outcomes of investigations;

- feedback from individuals who have used the arrangements;”

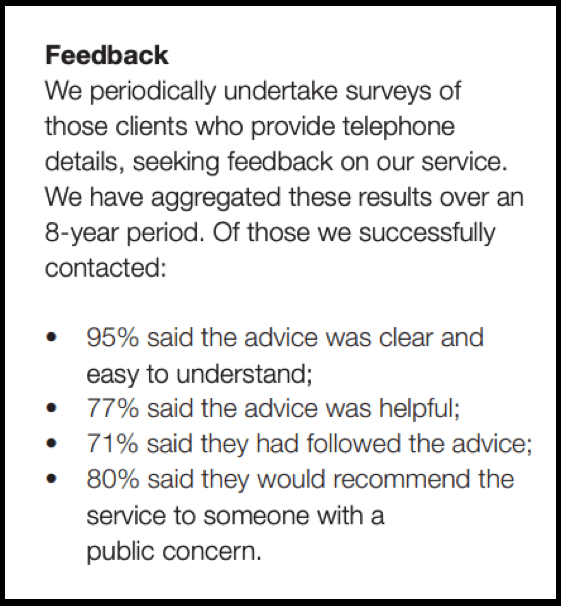

I am not aware of comprehensive published data on how whistleblowers experience Protect’s services. Some data appeared in Protects’ 2010 report on ten years of PIDA:

In its 2017 annual report, Protect briefly reported that 86% of people who had called the helpline in the previous year had said they would recommend the service to ‘someone with a workplace whistleblowing dilemma’.

Anecdotally, I hear more from whistleblowers who express disappointment and who perceive limited support from Protect. To some extent, this could be perhaps anticipated given the parameters of the situation; desperate whistleblowers searching for refuge in the context of toothless law that does not protect but allows further abuse, rubbing up against a non-statutory organisation with limited resources, that has no powers at all.

A few cases which offer interesting points of law are scooped up by Protect which is fair enough. Cases are also used to promote the organisation and used for good news stories – perhaps not so fair enough. Hero-innovator narratives may be good for raising organisational profile, but sober policy arguments about deaths and egregious failures of weak law may be preferable. Protect similarly may approach figures and whistleblowers who might be seen to be useful because of their profile to join as trustees. The response is not always affirmative. Run-of-the-mill whistleblowers however, sometimes report a less solicitous attitude.

It would be basic good practice for Protect to hold itself to the same standards that it says it expects from others, and to publish comprehensive data on how whistleblowers experience its services with broad details of what it actually does for them.

Protect has not in my view been radical in campaigning for better law. Twiddling at the edges with esoteric tweaks of the existing legislation has had limited impact on the continuing failures of public protection. Protect has repeatedly made recommendations to strengthen, but not to replace the legislation. When legislation was revised by the government, Protect’s 2014 submission suggested various tweaks, some important, but it did not say the most important thing of all. That is, the law ignores whistleblowers’ concerns and does not compel anyone to investigate them.

There was tangential reference to the investigation of whistleblowers’ concerns in that Protect’s 2014 submission proposed the introduction of a code of practice.

Protect’s draft code of practice from its 2013 ‘Whistleblowing Commission’ report included a standard on responding to whistleblowers’ concerns and keeping whistleblowers informed of investigation plans and outcomes. This was not the same as clear compulsion of investigation with mandatory timescales.

Protect’s tweaking tendencies are less threatening to power. A lack of radicalism can help to keep a place at the table. A charitable interpretation might be that Protect feels it can be more effective inside. Indeed, it is inordinately difficult to get any hearing from power on whistleblowing matters. But it is a question of the price of that audience.

Six hundred and fifty six lives were lost at Gosport, most of which occurred after whistleblowers were suppressed. They throw into sharp relief the question of where the balance should be struck in challenging power. How much compromise is worth a place at the table for influence over future law? PIDA has been in force for twenty years. Twenty years of recurring disasters and deaths due to poor whistleblowing governance. It is fair to say that alacrity has not been the watch word.

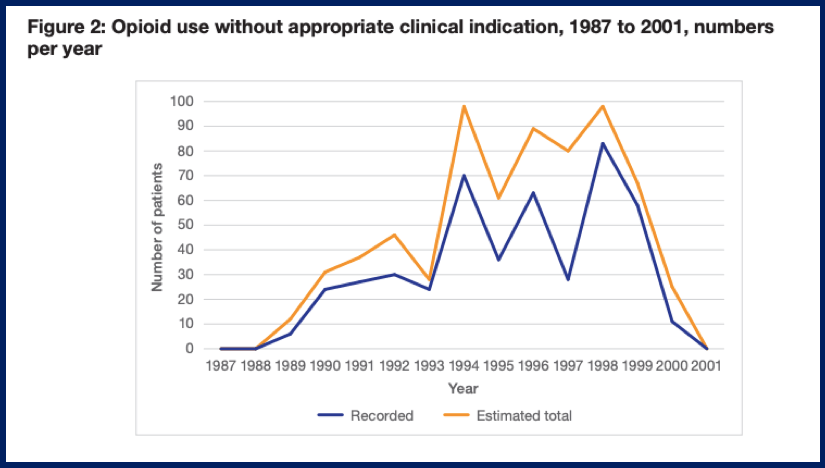

Timeline of inappropriate opioid use at Gosport War Memorial Hospital, which has been linked to 656 unnatural deaths by the panel investigation:

Source: Report of the Gosport Inquiry

Source: Report of the Gosport Inquiry

Protect now endorses the government’s sham Freedom To Speak Up project.

Some may wonder if this is commercial flattery.

Protect’s CEO and I briefly debated some favourable comments that she made about Freedom To Speak Up Guardians at a specialist conference on 20 June 2018 about Twenty Years of PIDA.

A Protect trustee has now gone into glowing print about the debatable merits of the Freedom To Speak Up project:

| Whistleblowing: public services fail to deliver on promise of open culture

‘It is true there has been progress. Following the 2015 review of health service whistleblowing by Robert Francis QC, there is now a network of “freedom to speak up guardians” across NHS trusts, supported by a national guardian for the health service, a post energetically filled by Dr Henrietta Hughes. Her first report, published in September, reveals that more than 7,000 cases were raised with freedom to speak up guardians over the previous year. A third involved patient safety and service quality, and 361 people alleged they had suffered at the hands of their employer as a result of raising concerns. That thousands of people feel able to approach the guardians – albeit a fifth of them anonymously – is promising, and Hughes pushing for action at the trusts that failed to record any cases is a good sign.’

|

This article coincides with an inadvisable and manipulative publicity stunt by the National Guardian’s Office viz. ‘Speaking Up Month’, just before the government’s response to the Gosport Inquiry report and the annual collection of data for the NHS staff survey.

The endorsement of the government’s woeful and harmful whistleblowing policy is problematic for many reasons. Praising the project effectively endorses his own organisation’s contribution to the project.

The article cited statistics from the National Guardian’s Office. This data is flawed and unverified:

Another health check on the quality of the National Guardian’s data

Indeed, I wrote to parliament about a mission critical failure by the National Guardian to gather any data at all about whether whistleblowers’ concerns are addressed.

Parliament has acknowledged that this is a matter that needs to be pursued.

Even the Health Service Journal, not always a friend to whistleblowers, reported on 27 September 2018 about the National Guardian’s disinterest in whether whistleblowers concerns were addressed.

Over a week after HSJ’s coverage, the Protect trustee did not acknowledge this. This omission mirrored Protect’s inaction on PIDA’s failure to compel investigation of whistleblowers’ concerns.

The article made passing reference to the law:

“…the whistleblowing legislation itself needs strengthening”

Strengthening. Not wholesale, radical reform. This is even despite PIDA’s core failure to require the investigation of whistleblowers’ concerns or to compel anyone to protect whistleblowers. Even in the terrible shadow of Gosport.

As far as I can see, Protect remains perched on the fence. Lip service, tweaking, and endorsing the biggest block to real reform – the Freedom To Speak Up project, which the government is trying to spread and embed. Once embedded, undoing it will be a devil of a job.

Of interest, Protect’s former Head of Legal Services is now National Engagement Manager at the National Guardian’s Office, taking cross fertilisation to a different level. She has contributed to the National Guardian’s publicity material, for example, through a newsletter:

In short, you can have all the technical expertise and knowledge in the world. But how much is it worth if your compass doesn’t work.

It is time for any fiefdoms built on mutual interests to be challenged. The public interest must always reign.

A properly independent statutory body with duties and powers is needed to protect the public and whistleblowers, not private bodies partly paid for by the public that will not – or feel unable – to fully challenge power.

An independent, statutory body with proper reporting duties, duties of transparency, duties under FOI, duties of Equality, duties to account for how it gets its money and uses it, and duties to answer to parliament.

UPDATE 30 DECEMBER 2019

Protect as ever has rushed to congratulate the government as represented by the NHS National Guardian, who has dubiously been awarded an OBE in the New Year’s honours.

Protect recently lost its most recent CEO under unclear circumstances. An initiative that was started under her tenure – a proposal for “reforming” UK whistleblowing law nevertheless continues. The proposal is likely to please the government as it does little to improve governance and leaves employers in a still overly powerful position, that would allow abuses to continue.

This is a response by colleagues and me to Protect’s tepid proposal:

Response to Protect’s proposed changes to UK whistleblowing law

RELATED ITEMS

Replacing the Public Interest Disclosure Act

UK Whistleblowing Law is an Ass: Helen Rochester v Ingham House and the Complicit CQC

Thanks Minh. Another incisive and informative contribution. Trivial comment, I think there might be a word (? ‘difficult’) missing after ‘inordinately’. Best Hugh

LikeLike

I have had nothing to do with PCaW /Protect on my journey as a care home whistle blower so cannot comment on them other than they do not have investigatory powers. I went to the prescribed person, the CQC twice, when it was obvious my employers were not going to investigate my safety and care concerns.

I expected CQC, who do have investigatory powers, to do so in a timely and thorough way. Wrong on both occasions!!

On my first occasion it took them nine months and then a referral from the NMC that backed my concerns before they even turned up at the home. On my second it took three months and my appearance at their board meeting before they paid lip service to inspecting the home on standards at night. They pitched up at 6am instead of the previous 8pm when the shift started.

CQC and the renamed Protect have one thing in common however. They can and do both talk to employers at the same time as speaking to the WB. Again I cannot comment on Protects actions either in the Dr Day case or otherwise but in my experience the CQC will side with the employer breaching confidentiality or making suggestions on how to treat the WB detrimentally the employer had not thought of.

My case is well publicised on this as are others. That needs to change as the law does not protect a WB on this conduct from the regulator.

There is only one independent charity supporting WB’s that I’m aware of and that’s Compassion in Care run by Eileen Chubb. They have nothing to do with employers whatsoever and are not funded in the way Protect is.

As for actually investigating WB concerns how many deaths or NHS/care home scandals do the government need before they change the law on whistleblowing and then rigorously enforce it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you sit on the fence Dr A will see you!

LikeLike